By Peter Henry Emerson

“So British Public, who may like me yet,

(Marry and Amen!) learn one lesson hence

Of many which whatever lives should teach

This lesson, that our human speech is naught,

Our human testimony false, our fame

And human estimation words and wind.

Why take the artistic way to prove so much?

Because it is the glory and the good of Art,

That Art remains the one way possible

Of speaking truth to mouths like mine, at least.”

Browning.

Art is a language, and pictorial art is the expression by means of pictures of that which man considers beautiful in the world around him. The misconceptions and consequent confusion in men’s minds concerning art matters are chiefly due to the literature of the subject. From the time of the Rhetoricians of the Roman Empire to that of the Rhapsodists of the present day, the majority of these writers have been laymen. They have discussed art from the literary standpoint, whilst artists have, as a rule, kept silent, and only expressed their opinions by their works, the few who have written, writing rather for artists than for the public. Hence the unthinking have lead their opinions formed for them, and as these opinions were evolved from the inner consciousness of the writers, and were not based on any logical first principles, it necessarily followed that they shifted like a weathercrock.

What, then, is the first principle of all art? A study of the rise and fall of the art of the different schools from the earliest times to the present day, clearly shows what that principle is, namely, a faithful adherence to Nature, for there is no such thing as abstract beauty in colour or form. The crude rock-scratchings of the stone age were naturalistic. In Ancient Egypt, during the early period of art, before it became canon-hampered, the work was better than at any subsequent period, for from the time of the middle kingdom, canon, tradition, and priestcraft enslaved art, and nature was neglected. In Babylon and Assyria there was an advanced over Egyptian art, simply because nature was more studied. In Greece, where sculpture and painting reached such heights under Praxiteles and Apelles, the study of nature was the watchword, and gradually, as artists fell away from the study of nature, art declined, until it reached its lowest depths in the slavish work of the Early Christian and Mediaeval painters. With Cimabue and Giotto a fresh feeling for nature returned and this germ gradually grew and developed during the period of the Renaissance, in the works of the Van Eycks, of Memling, Quentin Matsys, Durer, Holbein, Massaccio, Ucello, Perugino, Mantegna, Bellini, Da Vinci, Michael Angelo, Andrea del Sarto, Raphael, Carreggio, Giorgione, Titian, and others. But this development never reach perfection, and although the Renaissance artists got nearer to nature, yet they were not perfect, and it was reserved for Salvator Rosa, Claude Lorraine, Canaletto, Velasquez,  Ribera, Poussin, Rubens, and above all Teniers, De Hooge, and Rembrandt, to make a further advanced. Velasquez and the Dutchmen especially stand out as giants of their age. Curiously enough in Japan, too, art went through different stages until it culminated in the naturalistic school of Shiju. But in Europe the artists above-mentioned only prepared the way for John Constable in England, and after him, in France, Rousseau, Corot, Millet, and, greatest of all, Bastien Le Page, the greatest painter that has ever lived, because the greatest naturalist. The evidence is to our mind conclusive that wherever the artist has been true to nature, art has been good; wherever the artist has neglected nature and followed his imagination, there has resulted bad art. Nature then should be the artist’s standard. But even when he remains faithful to his creed his scope is limited, for, as Professor Helmholtz says, in reproducing nature one of the chief things to be taken into account is the quantitative relation between luminous intensities. Now, as Helmholtz clearly shows, the painter with his white lead of the photographer with his white paper is unable to imitate the brightest sunlight, he must therefore paint in a lower gamut or tone, that the ratios of the luminous intensities may be true. Thus, then, there are subjects which if painted in nature’s scale or tone would give several things in the picture black and sever others white, which were not so in nature, and in this way the picture would be untrue. Neither painting nor photography can depict such subjects truly, they are therefore better left alone. Now, curiously enough, there has been for a long time a prejudice among the unthinking public against photography, chiefly because it has been called a mechanical process. Much has been written against it by incompetent photographers who, at the same time, never rose beyond mediocrity in the branches of the art they professed. One of these has stated that its results are false in local colour. This may have been true when he wrote,

Ribera, Poussin, Rubens, and above all Teniers, De Hooge, and Rembrandt, to make a further advanced. Velasquez and the Dutchmen especially stand out as giants of their age. Curiously enough in Japan, too, art went through different stages until it culminated in the naturalistic school of Shiju. But in Europe the artists above-mentioned only prepared the way for John Constable in England, and after him, in France, Rousseau, Corot, Millet, and, greatest of all, Bastien Le Page, the greatest painter that has ever lived, because the greatest naturalist. The evidence is to our mind conclusive that wherever the artist has been true to nature, art has been good; wherever the artist has neglected nature and followed his imagination, there has resulted bad art. Nature then should be the artist’s standard. But even when he remains faithful to his creed his scope is limited, for, as Professor Helmholtz says, in reproducing nature one of the chief things to be taken into account is the quantitative relation between luminous intensities. Now, as Helmholtz clearly shows, the painter with his white lead of the photographer with his white paper is unable to imitate the brightest sunlight, he must therefore paint in a lower gamut or tone, that the ratios of the luminous intensities may be true. Thus, then, there are subjects which if painted in nature’s scale or tone would give several things in the picture black and sever others white, which were not so in nature, and in this way the picture would be untrue. Neither painting nor photography can depict such subjects truly, they are therefore better left alone. Now, curiously enough, there has been for a long time a prejudice among the unthinking public against photography, chiefly because it has been called a mechanical process. Much has been written against it by incompetent photographers who, at the same time, never rose beyond mediocrity in the branches of the art they professed. One of these has stated that its results are false in local colour. This may have been true when he wrote,  but since the introduction of orthochromatic plates, and the process of photo-engraving, the accusation is no longer just. By photography the relative values can now be rendered quite correctly. Another charge brought against it was falseness of perspective, or drawing, we presume they mean. This any good photograph will promptly refute, no other evidence is required. The idea of the falseness of perspective arose from the fact, that some photographers, by an ignorant use of the lens, produced distortion, and we can only say that the critic who advanced such a theory, if a photographer himself, must have been a very incompetent one, and his opinion on matters photographic therefore valueless. We know of no objections having been brought against photography as a means of artistic expression by any practical artist of genius or even repute, and for the opinion of mediocre artists we are little.

but since the introduction of orthochromatic plates, and the process of photo-engraving, the accusation is no longer just. By photography the relative values can now be rendered quite correctly. Another charge brought against it was falseness of perspective, or drawing, we presume they mean. This any good photograph will promptly refute, no other evidence is required. The idea of the falseness of perspective arose from the fact, that some photographers, by an ignorant use of the lens, produced distortion, and we can only say that the critic who advanced such a theory, if a photographer himself, must have been a very incompetent one, and his opinion on matters photographic therefore valueless. We know of no objections having been brought against photography as a means of artistic expression by any practical artist of genius or even repute, and for the opinion of mediocre artists we are little.

But let us for a moment look at the other side of the question. We read in Algarotti’s Essay on Painting, written in Italian in 1744, when speaking of the Camera Obscura, Da Vinci’s invention: “The best modern painters amongst the Italians have availed themselves greatly of this contrivance; nor is it possible they should have otherwise represented things so much to the life….. It is probable, too, that several of the Tramontaine masters, considering their success in expressing the minutest objects, have done the same. Everyone knows of what service it has been to Spanioletto (Ribera) of Bologna, some of whose pictures have a grande and most wonderful effect.” Here, then, is evidence that Spanioletto and other great masters thought highly of the Camera Obscura; they did not discover any falseness of perspective. Again, Jean François Millet in a letter to his friend Feuardent, dated April 7th, 1865, writes telling him to bring photographs of sculptures from the antique, and certain paintings, and he goes on to say: – “In fact, bring whatever you find, figures and animals. Diaz’s son, the one who died, brought some very good ones, sheep among other things. Of figures, take of course those that smack least of the Academy and the model, – in fact, all that is good, ancient or modern.” This, then, is the esteem in which photographs were held by one of the greatest of painters, ancient or modern. Had it not been for jealousies and commercialism, photography would, without doubt, have long ago held a high and honourable place as a fine art, for when the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain was founded in the year 1850, Sir Charles Eastlake, at that time President of the Royal Academy, was also elected the first president of the new Society, whilst Sir W. Newton, a miniature painter of repute, was elected its Vice-President. In the list of members were to be found the names of many artists of repute. At that time Photography was, as it is now, practiced by many artists, and there was even an idea of making a training school in connection with the Academy Schools of Art, the students were to be divided into classes, viz., artistic and scientific, but not student was to be admitted into either class until he had passed a certain standard of excellence. One of the oldest living photographers has written that the bright future of photography was marred by the blasting hand of commercialism which has ruined so much in other branches of art. At any rate the evidence is clear enough that had the artists and scientists who were the promoters of the first English Photographic Society held their own, photography today would probably have been practiced by artists and scientists alone – a noble and learned profession – instead of being practiced, as is now only too often the case, by illiterate and ignorant tradesmen.

To come down to the actual present, more than one able painter has told us that he prefers a first rate photograph as a work of art to a second rate painting or sculpture, and most severely critical are the painters referred to. Another. T.F. Goodall, an able naturalistic painter, has written the following on photography: “Photography has undoubtedly played an important part in the development of modern art, both in figure and landscape…. Hitherto the chief aim of the photographer seems to have been a biting sharpness of detail in the negative, which is generally quite fatal to the result form an artistic point of view, for in breadth lies the beauty and the sentiment of landscape…. There is no reason why photography in capable hands may not be made a means of interpreting nature second only in value to painting itself, destined to supersede all other black and white methods in bringing an extended knowledge of and taste for art to the masses of the people. The prejudice existing against photography arises from the fact that hitherto it has been worked merely as a mechanical process; but if by results it can show that it is worthy, it will rank as a fine art… There should be a great future for photography if followed on really artistic lines. It should be hailed as a most powerful ally by the modern school of painting, as by means of it people may be taught to perceive how false are many of the pictures they believe in, and how much more beautiful and interesting is truth. From an art-educational point of view its value can scarcely be overrated; much less has been done be photogravure and other processes of reproduction, to spread a knowledge of pictures, and there is no reason why the same methods should not be used for original work. A good photogravure is to be preferred to a bad painting or second-rate engraving, and is incomparably better that the odious chromos and wretched prints with which so many walls are disfigured. If, instead of being satisfied with mere topographical views of foreground studies, the photographer has cultivated artistic feeling, means are at his command for communicating to others what has impressed himself, and he may produce work of permanent value. Everything depends on what he finds to say how he tells it. If the operator has artistic insight it will show itself in his negative, just as it would on his canvas if he were a painter. The mechanical and chemical processes, the practised judgement necessary in timing his exposures, the skill and knowledge requisite in developing his plates, these are his technique; but the art value of the result will depend on  what he communicates to us by its aid. As long as his ideas of pictorial art are confined in landscape to views of churches and ruins, rustic bridges and waterfalls, or topographical views of the haunts of tourists, taken from the guide-book point of view, and in figure to artificial compositions, reminding one of an amateur theatrical performance, so long will his work be destitute of artistic qualities, and, therefore, valueless; but if he brings to his work a genuine appreciation of the picturesque in landscape and figures, and a knowledge of how so to place a subject on his plate as to convey his impression to others, he may produce most beautiful and meritorious results. He must learn, as the painter has to do, to distinguish what in nature is really suitable for pictorial purposes, on account of beauty of form, or tone, or light and shade, from what merely gives him pleasure by some quality which, however impressive in nature, it is not possible to transfer to canvas. A picture being a design enclosed by four straight lines, can only please and impress by certain suitable decorative qualities in the subject. Nothing, for instance, is more delightful than to be in a shady wood on a summer’s day, but a picture of the wood will not reproduce the pleasurable physical sensations we feel on the spot, and must depend for its success on aesthetic properties quite distinct from them. Many a spot may be quite charming from the picnic point of view, but totally unsuitable for pictorial purposes. To know what will make a picture is one of the most difficult secrets in landscape art; knowing just how much of a scene to take in, where to begin and where to end, decides whether the result will convey a distinct and complete impression, or be merely a haphazard study.”

what he communicates to us by its aid. As long as his ideas of pictorial art are confined in landscape to views of churches and ruins, rustic bridges and waterfalls, or topographical views of the haunts of tourists, taken from the guide-book point of view, and in figure to artificial compositions, reminding one of an amateur theatrical performance, so long will his work be destitute of artistic qualities, and, therefore, valueless; but if he brings to his work a genuine appreciation of the picturesque in landscape and figures, and a knowledge of how so to place a subject on his plate as to convey his impression to others, he may produce most beautiful and meritorious results. He must learn, as the painter has to do, to distinguish what in nature is really suitable for pictorial purposes, on account of beauty of form, or tone, or light and shade, from what merely gives him pleasure by some quality which, however impressive in nature, it is not possible to transfer to canvas. A picture being a design enclosed by four straight lines, can only please and impress by certain suitable decorative qualities in the subject. Nothing, for instance, is more delightful than to be in a shady wood on a summer’s day, but a picture of the wood will not reproduce the pleasurable physical sensations we feel on the spot, and must depend for its success on aesthetic properties quite distinct from them. Many a spot may be quite charming from the picnic point of view, but totally unsuitable for pictorial purposes. To know what will make a picture is one of the most difficult secrets in landscape art; knowing just how much of a scene to take in, where to begin and where to end, decides whether the result will convey a distinct and complete impression, or be merely a haphazard study.”

Is more evidence required? We think not; and we emphatically re-assert what we have previously put forward that as a means of artistic expression the camera is second only to the brush – how successful the artist is with either depends entirely upon himself. All we ask is that the results shall be fairly judged by the only true standard – NATURE, and the only knowledge required by the public for a true and thorough appreciation of pictures is a knowledge of Nature, which can only be obtained by studying her. Such knowledge is not to be found in books, and as William Hunt says: “John Ruskin’s receipts make a book, but they never made a painter, and will never make a picture.”

We have adopted a reproductive process for publishing these plates. This process is variousy named and worked with different modifications by different firms, but essentially it is an automatic etching on copper, as first discovered by Nièpce. If successfully performed it is purely an automatic process, so that the resulting copper plate is a facsimile of the negative, no translator stepping in to mar the work. All the plates in this portfolio are printed from copperplates produced in this way directly from our original negatives. The plates are, as a rule, entirely free from retouching, and any hand-work that has been introduced is a cause of regret to us, and we are in no way responsible for it, for our idea of a perfect photo-etching or engraving process is one in which the resulting copper plate is entirely the effect of chemical action. The beauties of nature are far too subtle to be improved upon even by artists of the greatest technical abilities. These processes have, as a rule, been used hitherto solely for reproducing paintings, and for that purpose they are immeasurably superior to line engraving or etching, for the original work does not suffer in translation, which is of vital importance. These plates have been reproduced from our negatives by The Type-Etching company (Messrs A. and C. Dawson), Messrs, Boussod, Valadon and Co., Messrs, Walker and Bontall, and The Autotype Company. Nos. 3, 4, 6, 11, 14, 16, 17, and 19 being Messrs. Dawson’s work, Nos. 1, 2, 5, 8, 9, 10, 13, and 20 being Messrs, Boussod, Valadon and Co’s work, Nos. 7, 12, and 18 being Messrs, Walker and Boutall’s work, and No. 15 being the Autotype Company’s work.

Each plate is separately copyrighted.

P.H. EMERSON.

January, 1887,

Bedford Park, London, W.

Table of Plates.

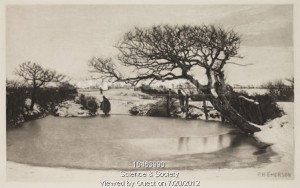

- A Winter’s Morning

- A Dame’s School

- A Spring Idyl

- The Mangold Harvest

- Confessions

- The Grafter

- A Misty Morning on the North Sea

- On Southwold Marshes

- A Suffolk Dike

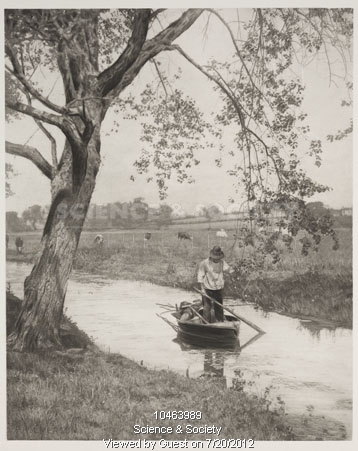

- Crusoe’s Island – River Granta

- The Poacher

- Sunrise at Sea

- At Plough – The end of the furrow

- On Breydon Water – Sea-fog coming up

- Going to Market – A Winter Scene

- The Stickleback Catcher

- An Autumn Pastoral

- In the Barley-Sele

- The Faggot Cutters

- A Fisherman at Home

All images copyright Science and Society.

Sources :

Flickr: http://www.flickr.com/photos/nationalmediamuseum/sets/72157606886702305/with/2780137385/

Science and Society: http://www.scienceandsociety.co.uk/